I am an emergency physician. It is the best job in the world and I am proud to do it. However, recent media reports paint my colleagues and me as the source behind the recent dramatic rise in prescription drug abuse. We aren’t. Despite certain perceptions to the contrary, we actually account for a very low percentage of all narcotics prescribed.

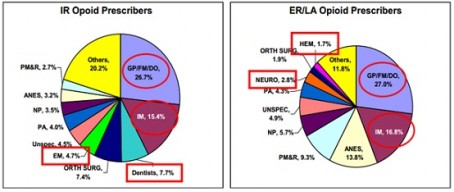

Key: IR = immediate release; ER/LA = extended release/long-acting; EM = emergency medicine

- General Practitioner/Family Practitioner/Doctor of Osteopathy and Internal Medicine were the top prescribers for immediate release and long-acting opioids

- Immediate-release opioid prescribers:

- Dentists and emergency medicine specialists accounted for about 7.7 percent and 4.7 percent of all immediate-release prescriptions for opioids

Source: U.S. Food and Drug Administration: Presentation: Outpatient Prescription Opioid, Utilization in the U.S., Years 2000 – 2009, July 22, 2010

Even when we write narcotic prescriptions, we do so for a limited supply, knowing our acute pain patients will need to follow up with other physicians for more definitive treatment.

Precisely because we are on the front lines of the battle against this scourge every single day, emergency physicians have a vested interest in keeping unnecessary prescription drugs off the streets. The number of emergency department visits related to prescription drugs now exceeds those from cocaine and methamphetamine abuse combined. We see the tragedies and the near-tragedies of this epidemic every day in our ERs. The victims are never just the patients who have overdosed – every one of them has family and friends who are negatively affected by the damage and deaths caused by prescription drug abuse.

Our challenge as emergency physicians is to strike the balance between providing needed pain control and keeping the public safe.

For that reason, we employ a variety of techniques, from checking government databases to good old clinical judgment to separate those who need narcotic analgesia from those who may be seeking these drugs for purposes of abuse. Studies demonstrate that emergency physicians are actually quite good at making these determinations.

But there are still significant challenges to curbing our nation’s addiction to prescription narcotics. First and foremost, even when addiction is proven there are very few resources to aid in recovery (assuming that the addicted patient is ready to begin that process).

Second, significant pressure is placed on emergency physicians to improve customer satisfaction. Some physicians are docked pay or even fired based on the results of patient satisfaction surveys. When challenging a patient regarding their drug-seeking behavior it is not uncommon to hear a retort of “I’m going to give you a bad survey” or “I’m calling the hospital’s complaint line.” If the physician faces the loss of pay or even the job over a “bad survey,” how are they likely to respond? What would you do?

This “customer satisfaction” focus creates a significant disincentive for emergency physicians to hold fast against the onslaught of drug seekers. We have significant powers of persuasion with our patients, but there are always those determined addicts who will stop at nothing to feed their addiction. Every emergency physician has treated them.

So what can be done? First, we need to improve access to primary care providers so that patients with chronic painful conditions can be managed in a consistent manner. Second, we need to allow emergency physicians to refer chronic pain patients to their primary care providers without prescriptions for narcotic medications and without repercussions from the dreaded “surveys.”

Lastly, we need to improve access to mental health and addiction recovery services, so that we can provide addicted patients the assistance they really need instead of the drugs they want.

Howard Mell, MD, FACEP

Emergency physician

American College of Emergency Physicians